Our Red Bull Rampage article was featured on Singletracks.com! Check it out on our site (scroll down), or there – whichever you prefer!

Psyche and injury are undoubtedly connected. Throw in the stresses associated with an intense sporting event and a fine line develops between victory and a potentially deleterious disaster. Red Bull Rampage is the extreme of the extreme – how do you mentally prepare? Can you? Turning fear into fire is only one part of the overall recipe. To assess the variety of components involved in sports like enduro, downhill and freeride mountain biking, an accurate measurement of all ingredients is necessary to ice the cake. Skills, strength, the ability to traverse technical terrain… and that catchy cerebral aspect… when your task is to successfully 360 down a 40-ft drop, mental agility and self-awareness are absolutely vital for success.

The science of sports psychology is decently clear. Taking an anecdotal approach to analyze the physical outcome driven by the study of the mind can also prove to be invaluable. Rampage – it’s absolutely begging for an investigation (hell yeah). The freeride mountain bike event is one of the most intense competitions in the world, with riders using dedicated course terrain to build their lines… think of it as a natural “bike park,” descending cliffs and near-vertical sandstone ridges all while pulling off backflips and suicide no handers. You name it, they ride it. Premier definition of fear into fire.

The marriage between an unforgiving landscape and stylishly difficult tricks begs a rider to hit a line too fast, too slow, catch a lip at the wrong angle – ending a run early. They know this going into it. Maybe the athlete will walk away unscathed, maybe not at all. In 2012, Paul Basagoitia traveled to southern Utah to attempt a natural terrain double backflip, sustaining a concussion in the process and kissing the ground during several other attempts before he actually accomplished his goal (see video below). During Rampage 2014, the late Kelly McGarry backflipped over the +70 ft. Canyon Gap, crashing hard upon landing. A year later, there were so many issues that – fast forward to now – Red Bull decided to change up the rules to use a fully natural terrain format (no build-in structures like wooden ramps). But even with that limitation, the sport is not forgiving.

Let’s take a look at what happened during Rampage 2016. Logan Binggeli, Brendan Fairclough, Kurt Sorge… all crashed this year during practice. Imperfection. In fact, I almost got taken out by Sorge on Thursday after he popped a transition lip too high, sliding into a berm about 5 ft to the left of where I was standing and bounced off his bike. The impact sustained was physically heard, but he stood up without hesitation and brushed off his red jersey. A few minutes later, Graham Agassiz successfully completed the same transition, stopping next to Sorge:

Sorge: “Bars straight to the thighs. Oh man,” he laughed and shook his head.

Agassiz: “Are you ok?”

Sorge: “I’m alright. I think,” he said. “I just popped it.” ::knuckles to Agassiz:: “Thank you, SUNTOUR.”

Fast forward a few hours. As I walked into the River Rock Roasting Company to grab a cold brew and medicate my writer’s block, I saw Fairclough and his crew standing in line. Friendly waves were exchanged. “So. How are y’all doing?” I asked. They looked tired, and it was mutually understood what the question regarded. Conversation was light, good, positive, short… coffee. Wrists taped and covered in a layer of Virgin dirt, you’d never guess he crashed over a monstrous canyon gap during practice the day before and would forfeit his participation. A similar ending for Logan Binggeli – he dropped out after suffering a concussion, unsuccessfully landing a near-vertical drop. It was difficult to stand there and watch him fall so far and so fast, the medics dressed in neon yellow shirts responding immediately, running up toward the cloud of dust, obscuring the rider and his bicycle.

Arrive: Friday. Rampage. The wind became a major concern with gusts up to 23 mph. The flags were visibly blowing atop the start. Delays existed between riders, waiting on the wind, necessary for safety. Several athletes were unable to complete the bottom portion of their run, most notably during the second run of the day. It’s impossible to speculate why – it could be the natural difficulty of the event, it could be a small disturbance in peace of mind due to the wind – who knows. All but one just brushed themselves off, raising their arm to signal a “hell yeah,” walking or riding off course. Agassiz missed landing a 360 over a large transition, suffering a pelvic fracture. But even as he was loaded up and strapped into a vehicle to be quickly driven off course, he threw up metal horns to the surrounding crowd. An outward effort symbolizing resilience.

Fueling the Fire, Minding the Mind.

From an outsider’s perspective, all of the athletes embraced a positive cognizance, regardless of the outcome (injury or not). Resilience is not genetic – we actually do not know why some people gain strength and others lose from identical experiences. Depression and anxiety, and if the injury is repeated, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)… yes. It all happens. This is why the U.S. military has instated mandatory resilience training – to prevent the onset of the aforementioned disorders. Sports and tactics have a grave similarity (this is something I am personally familiar with). No one wants to be a part of the injury statistics reported in medical journals.

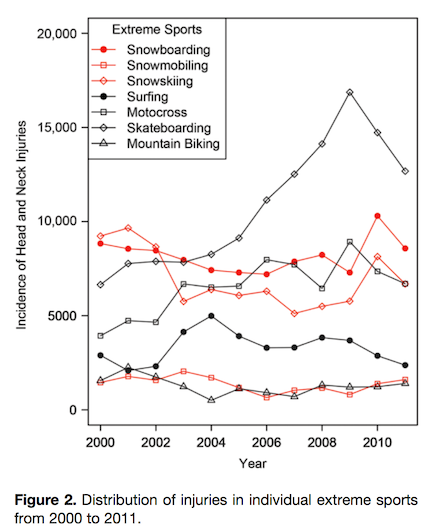

Simply connect the psychology behind preparation for competition with the physical reactions necessary for performance. The outcome can present itself anywhere across a spectrum, ranging from ideal (winning/completing the run) to physical injury and even death. In an investigative study conducted at the Western Michigan University’s School of Medicine, researchers tallied up a total of 4,083,691 injuries that were reported for athletes participating in both the Winter and Summer X Games between 2000 and 2011 (see figure below). Of those, 11.8% were head and neck injuries, with skateboarding taking home the prize for highest rate of incidence – mostly skull fractures. Earlier this year we lost a hero in the BMX world. Dave Mirra, with 24 X Games medals to his name, succumbed to a battle with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a disease that presents itself after repeated trauma to the head. The chronic degeneration of brain tissue due to concussions and other subconcussive injuries can eventually give way to behavioral changes such as anger and depression, impaired judgment, and the onset of dementia.

Considering the higher than average injury rates associated with extreme sports, it is obvious what fosters a major mental component of making it or breaking it (sometimes, literally). Previous experience – former injury, former failure – dictates mindset, and in some cases can create an association similar to PTSD. The stoke stuff is often a simple masquerade. The experience itself is actually terrifying, but no one can know that. It has to be hidden, and that creates a mindset where the only exposure is strength and fearlessness.

It would make sense that the more inexperienced an athlete and the more extreme the sport, the higher the risk and rate of injury. Furthermore, the higher rate of injury exacerbates the cultivation of stress associated with performance, which may or may not lead to issues in the future. A 2013 study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine followed 249 downhill riders, both elite and professional, over the course of one season to analyze rate and cause of injury. The most frequent location of injury was the lower leg, and nearly 41% of the reported total injuries kept the athlete off the bike for more than 28 days. The elite riders had a significantly higher rate of injury than the pros, and in addition, it was more likely something would happen during competition versus practice, with the majority of injuries being caused by riding errors.

In reality, no one can really reconcile a 75 ft canyon gap. Superhuman brains do not exist. Training effect either kicks in or it doesn’t. Time to contemplate the process immediately ahead isn’t there, therefore, reliance on previous autonomic knowledge is the only thing available. Simulation of the intense freeride mountain biking experience is maintained through repetitive practice via BMX dirt jumps, at bike parks and on downhill runs – the only thing that can somewhat allow the athlete familiarization with the concept of “large.”

Mood and stress are major predictors of orthopedic incidence and traumatic physiological events among all classes of athletes. This has been shown several times over. Psychometric prognoses have been analyzed in the research arena for many years, and scientists have come to the consensus that perceived stress, negative thought patterns, and chronic exposure to stressful life events elevates the risk of injury significantly. Interestingly enough, studies have shown a considerable reduction in injury and illness incidence (nearly half in some instances) when simple cognitive behavioral techniques have been emplaced and practiced.

Cultivating the Inner Chi

There are many, many tools in existence that can be used to address that “Oh shit!” feeling that creeps up during totally appropriate and realistic moments. The reaction is valid. It’s the body’s way of signaling it’s will to survive. Ripping a bike down and over a mega transition doesn’t compute according to the primal midbrain. Physical training can be pointless when the mind says otherwise, but adding the following tools to your repertoire can increase focus, decrease fear, anxiety and overall risk for injury.

Energy management. When you stumble, crash, etc., recognize and address the moment, then take action. Avoid wallowing in the fear, sadness or negative thought that may pop up after a failure. This cultivates perceived stress and increases cortisol levels. It may sound too easy, but use your energy productively. Reinterpret the situation and become aware of yourself. If it’s practiced over and over, it will become a learned habit – you choose your reaction.

Breathe. Think about your heart rate. If you’re aware of it, you can help control it. Focus on and think about the breath. How it flows in through the nose, down and into the lungs, filling them all the way to the bottom. Follow it back out. Notice the heart rate dropping as this simple technique is repeated. This is the mind-body connection in action.

Mental games. Use real-time mental games to realign your counterproductive focus off of the stressor and onto something that takes effort – productivity is therefore created and anxiety is reduced. These are done for a minute or two and are great during intense situations (like dropping down a 40 ft near-vertical line). Examples are the alphabet game (A apple. A apple, B banana. A apple, B banana, C carrot… etc.) and the categories game (i.e. name as many of the bones in the body as you can in two minutes).

Avoid catastrophizing. Catastrophizing – a large word for freaking out. Assuming your going to go financially broke, your spouse is going to leave and your house is going to burn down all because you made an error… is unrealistic. Control the monkey brain. Ask yourself what is the most likely outcome of the scenario and give yourself a reality check. If necessary, use some mental games (mentioned above) – these are often helpful.

Focus on positive thoughts. This can be done in the moment or as a daily, habitual reflection. Both are recommended. Keep a journal. How you think influences gray matter structure. Long term, neural synapses and neurotransmitter levels actually change in response to repeated and trained thought processes. The brain will physiologically adapt to support a positive mindset if a positive mindset is practiced. Many studies, as well as the fundamentals of the Buddhist religion, support this practice.

Remember: The mind-body connection is real. Taking care of what is upstairs will drive a better performance experience. Definitely mind the Rampage.

Photography credit: © Jennifer Corso, truPhys, 2016. (unless otherwise cited)

References:

Andersen, M. B., & Williams, J. M. (1999). Athletic injury, psychosocial factors and perceptual changes during stress. Journal of sports sciences,17(9), 735-741.

Arvinen-Barrow, M., & Walker, N. (2013). The psychology of sport injury and rehabilitation. Routledge.

Becker, J., Runer, A., Neunhäuserer, D., Frick, N., Resch, H., & Moroder, P. (2013). A prospective study of downhill mountain biking injuries. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2012.

Carmont, M. R. (2008). Mountain biking injuries: a review. British medical bulletin, 85(1), 101-112.

Galambos, S. A., Terry, P. C., Moyle, G. M., & Locke, S. A. (2005). Psychological predictors of injury among elite athletes. British journal of sports medicine, 39(6), 351-354.

Impellizzeri, F. M., & Marcora, S. M. (2007). The physiology of mountain biking. Sports Medicine, 37(1), 59-71.

Kronisch, R. L., Pfeiffer, R. P., & Chow, T. K. (1996). Acute injuries in cross-country and downhill off-road bicycle racing. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 28(11), 1351-1355.

Leddy, M. H., Lambert, M. J., & Ogles, B. M. (1994). Psychological consequences of athletic injury among high-level competitors. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 65(4), 347-354.

Nelson, N. G., & McKenzie, L. B. (2011). Mountain Biking–Related Injuries Treated in Emergency Departments in the United States, 1994-2007. The American journal of sports medicine, 39(2), 404-409.

Ortega, F. B., Ruiz, J. R., Gutierrez, A., & Castillo, M. J. (2006). Extreme mountain bike challenges may induce sub-clinical myocardial damage. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 46(3), 489.

Pfeiffer, R. P. (1994). Off-road bicycle racing injuries–the NORBA Pro/Elite category. Care and prevention. Clinics in sports medicine, 13(1), 207-218.

Sharma, V. K., Rango, J., Connaughton, A. J., Lombardo, D. J., & Sabesan, V. J. (2015). The current state of head and neck injuries in extreme sports. Orthopaedic journal of sports medicine, 3(1), 2325967114564358.

Williams, J. M., & Andersen, M. B. (1998). Psychosocial antecedents of sport injury: Review and critique of the stress and injury model’. Journal of applied sport psychology, 10(1), 5-25.

Terrific, insightful article. Extremely well-written