I overheard a conversation about a week ago between two women discussing their weight-loss plans. “My trainer told me that I will burn extra fat for 24 hours after I workout,” one stated confidently. It’s a common statement and belief passed around gyms, the internet, and even in educational institutions. There are good reasons for their conversation, as it holds some truth. The problem with this scenario is that… (sorry ladies)… it isn’t true for women.

There are several things we know that make the 24-hour excess fat burn concept inaccurate:

The modality of exercise (strength training, intervals, prolonged aerobic activity) has an affect. Apples are not oranges. Cycling is not powerlifting.

Biological sex plays a role. A HUGE role. I apologize for bursting this bubble if your soapy sphere was still intact, but if you are a female, your window of post-workout fat burning glory ends after about three hours. Dr. Anne Friedlander helped pioneer research analyzing sex-specific differences in fuel metabolism during exercise. Many other researchers have followed suit, including Dr.’s Greg Henderson and Mark Tarnopolsky, who have analyzed fuel use after exercise. Let’s dive into the nerd pool!

The benefits of conducting exercise to promote whole-body wellness are impossible to ignore, and physical activity is essentially “free” medicine. To maintain favorable cardiovascular health and body composition, both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American Heart Association (AHA) currently recommend adults perform 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week, as well as two days of strength training per week.

In response to the many benefits exercise provides, ample research has focused on analyzing substrate utilization (i.e. carbohydrate and fat use for energy production) during exercise with a variety of intensities and types, often using male subjects. Differences between the way men and women use fuel during rest and exercise have been a largely solid finding. We have learned that it is more difficult for females to alter body composition, even though they utilize more fat during submaximal (moderate-intensity) exercise when compared to males. This is due to evolutional favorability for females to maintain fat mass above 12-15% to sustain reproductive capability. In a notable animal study, Dr. Ron Cortright of East Carolina University, found that male rats had a lower whole body mass and fat mass compared to female exercised rats after the animals completed nine weeks of daily, self-selected exercise bouts. This is even with female rats having a higher overall energy deficit. Again… blame evolution.

Several factors contribute to the differentiation in fuel selection between sexes. After consuming a meal (called the postprandial state), estrogen (estradiol) is released, decreasing free fatty acid (FFA) oxidation. This promotes an increase in fat mass. According to Dr. Mark Tarnopolsky, who’s research focus includes mitochondrial disease and dysfunction, estradiol is also attributed to a decrease in glycogen (stored glucose) use during exercise. After the administration of a specific form of estrogen (17-β-estradiol) to men, the following observations were noted: a decrease carbohydrate and amino acid use during exercise, an increase fat utilization, and altered mRNA transcription factors associated with lipid metabolism, but not glucose metabolism. The change in fuel use and rates began to mimic those seen in females, reinforcing the association of estradiol with female fuel selection.

Substrate use during recovery.

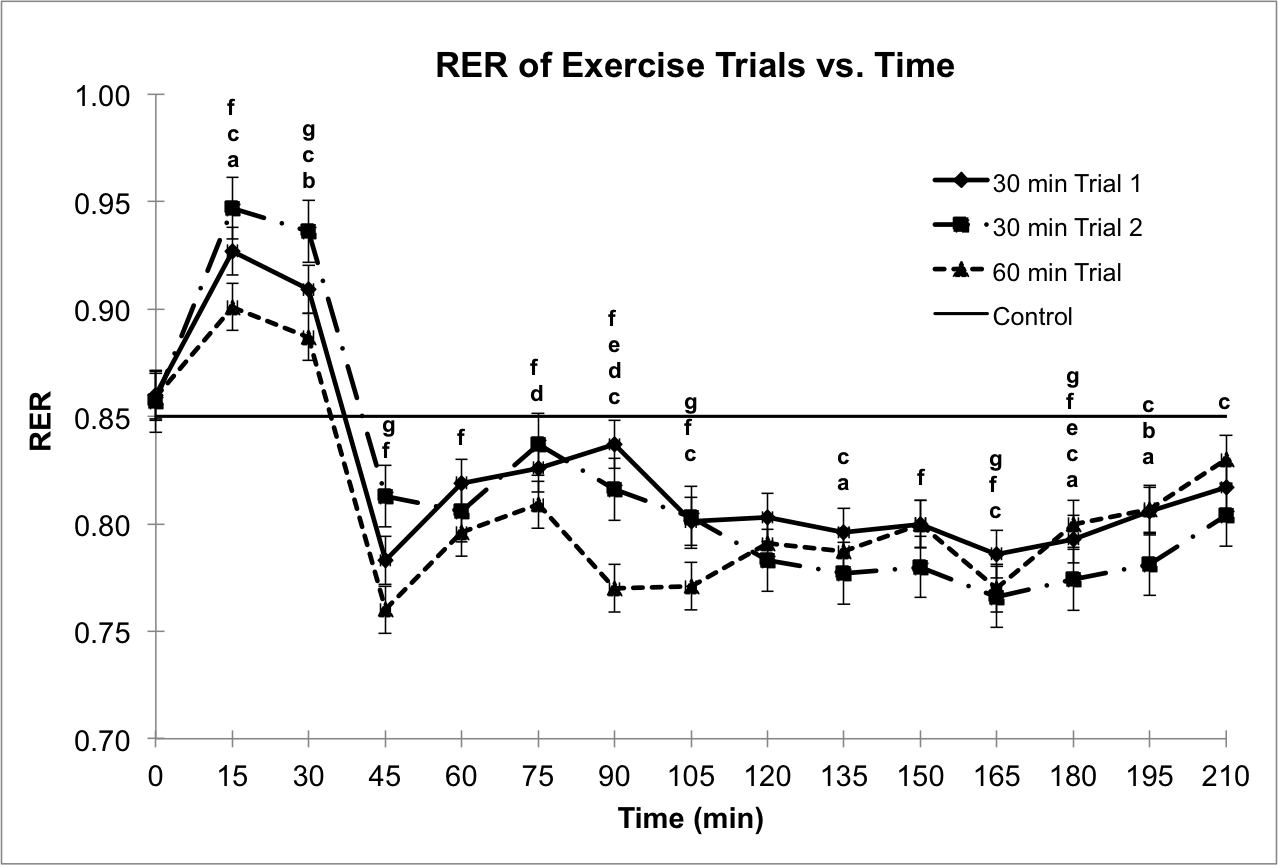

Few studies have explored substrate utilization during the postexercise recovery period, and differences have been distinguished between men and women. Excess postexercise oxygen consumption, called EPOC, is an increased rate of oxygen use (i.e. fuel use) after exercise ceases. People think of it as making up for the deficit caused by physical activity. Dr. Hiroyuki Imamura of Nagasaki International University, Japan, examined EPOC in females, with treatment varying exercise bout duration. This is where not only sex, but duration and intensity of exercise make a difference, too.

In her study, a 30 and 60 minute bout of exercise were conducted at 60% VO2max (moderate intensity), and significant differences in EPOC were found between the two trials. The differences in EPOC were seemingly correlated with the intensity of catecholamine (adrenaline and noradrenaline) response, and related to the duration of exercise, fatty acid availability, and use of fat both during and after exercise. In addition, the study had shown a significant rise in serum FFA immediately following the 60-minute bout of exercise, but not after the 30-minute bout of exercise. This means that more fat was being broken down and released into the blood for use after the longer exercise session.

Several studies conducted at the University of California, Berkeley, have analyzed postexercise fuel use, and researchers discovered significant increases in fat use in both sexes. However. It’s been noted that males who exercised on two separate occasions, 90 minutes at 45% VO2peak and 60 minutes at 65% VO2peak (so, low-moderate intensity, and moderate intensity, respectively), had increased fat use for 21 hours after both sessions. However, excess fat use in females was truncated, returning to normal resting values in nearly three hours. Additionally, the difference in intensities didn’t have an affect.

The conclusions here suggested that a shorter postexercise period of increased fat use in females assists in the maintenance of a higher essential body fat mass, an attribute inherent to the sex in order to maintain reproductive capability. We have now come full circle.

Well, what if women work out twice a day? Dr. Jack Azevedo and I attempted to answer this question. This is what we found. Multiple bouts of aerobic exercise completed in the same day (split or fractionalized sessions) do not have a substantial affect on total postexercise fat use in females. There is no “doubling your money,” here. Unfortunately, the duration of extra fat burn hasn’t been seen to be more than three hours in women, and we concluded the same.

The take away? Simply put, diet and exercise are the most important. If you want to change your body composition, analyze your dietary habits and see what needs to be changed (you can even hire us!) Instate a reliable exercise plan that targets your goals. But don’t rely on the “after-workout” to change your body.

References:

Achten J, Gleeson M, Jeukendrup AE (2002) Determination of the exercise intensity that elicits maximal fat oxidation. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 34:92-97

American Heart Association Recommendations for Physical Activity in Adults (2014) http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/PhysicalActivity/FitnessBasics/Americ anHeartAssociationRecommendationsforPhysicalActivityinAdults_UCM_307976_Article. Jsp. Accessed 27 December 2014

Barker, J. L. (2015). Lipid oxidation in females during the postexercise recovery period: One vs. two bouts of exercise. (Masters thesis, California State University, Chico).

Børsheim E, Bahr R (2003) Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Medicine 33:1037-1060

Casazza GA, Jacobs KA, Suh SH, Miller BF, Horning MA, Brooks GA (2004) Menstrual cycle phase and oral contraceptive effects on triglyceride mobilization during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 97:302-309

Cortright RN, Chandler MP, Lemon PW, DiCarlo SE (1997) Daily exercise reduces fat, protein and body mass in male but not female rats. Physiology & Behavior 62:105-111

Friedlander AL, Casazza GA, Horning MA, Buddinger TF, Brooks GA (1998a) Effects of exercise intensity and training on lipid metabolism in young women. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism 275:E853-E863

Friedlander AL, Casazza GA, Horning MA, Huie MJ, Piacentini MF, Trimmer JK, Brooks GA (1998b) Training-induced alterations of carbohydrate metabolism in women: women respond differently from men. Journal of Applied Physiology 85:1175-1186

Friedlander AL, Casazza GA, Horning MA, Usaj A, Brooks GA (1999) Endurance training increases fatty acid turnover, but not fat oxidation, in young men. Journal of Applied Physiology 86:2097-2105

Henderson GC (2014) Sexual dimorphism in the effects of exercise on metabolism of lipids to support resting metabolism. Frontiers in Endocrinology 5

Henderson GC, Alderman BL (2014) Determinants of resting lipid oxidation in response to a prior bout of endurance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 116:95-103

Henderson GC, Fattor JA, Horning MA, Faghihnia N, Johnson ML, Mau TL, Luke-Zeitoun M, Brooks GA (2007) Lipolysis and fatty acid metabolism in men and women during the postexercise recovery period. The Journal of Physiology 584:963-981

How much physical activity do adults need? (2014) http://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/everyone/guidelines/adults.html. Accessed 27 December 2014

Imamura H, Shibuya S, Uchida K, Teshima K, Masuda R, Miyamoto N (2004) Effect of moderate exercise on excess post-exercise oxygen consumption and catecholamines in young women. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness 44:23-29

Kuo CC, Fattor JA, Henderson GC, Brooks GA (2004) Lipid oxidation in fit young adults during postexercise recovery. Journal of Applied Physiology 99:349-356

Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD (2013) Deaths: Final data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports 61:1-117

Must A, Spadano J, Coakley EH, Field AE, Colditz G, Dietz WH (1999) The disease burden associated with overweight and obesity. JAMA 282:1523-1529

Nygaard E (1981) Skeletal muscle fibre characteristics in young women. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 112:299-304

Phelain JF, Reinke E, Harris MA, Melby CL (1997) Postexercise energy expenditure and substrate oxidation in young women resulting from exercise bouts of different intensity. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 16:140-146

Paoli A, Marcolin G, Zonin F, Neri M, Sivieri A, Pacelli QF (2011) Exercising fasting or fed to enhance fat loss? Influence of food intake on respiratory ratio and excess postexercise oxygen consumption after a bout of endurance training. International Journal of Sport Nutrition 21:48

Powers SK, Howley ET (2012) Exercise physiology. McGraw-Hill

Roepstorff C, Thiele M, Hillig T, Pilegaard H, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF, Kiens B (2006a). Higher skeletal muscle α2AMPK activation and lower energy charge and fat oxidation in men than in women during submaximal exercise. The Journal of Physiology 574:125-138

Tarnopolsky LJ, MacDougall JD, Atkinson SA, Tarnopolsky MA, Sutton JR (1990) Gender differences in substrate for endurance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 68:302-308

Tarnopolsky MA (2000) Gender differences in substrate metabolism during endurance exercise. Canadian Journal of Applied Physiology 25:312-327

Tarnopolsky MA (2007) Sex differences in exercise metabolism and the role of 17-beta estradiol. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40:648

Tarnopolsky MA, Rennie CD, Robertshaw HA, Fedak-Tarnopolsky SN, Devries MC, Hamadeh MJ (2006) Influence of endurance exercise training and sex on intramyocellular lipid and mitochondrial ultrastructure, substrate use, and mitochondrial enzyme activity. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 292:R1271-R1278

Wu BN, O’Sullivan AJ (2011) Sex differences in energy metabolism need to be considered with lifestyle modifications in humans. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism

I had a question about HIIT (high-intensity interval training) on our Facebook page, and whether or not this type of exercise would elicit a greater fat burn after exercise. In general, EPOC doesn’t comprise very much of the total energy expenditure from an exercise session. “Aerobic exercise protocols resulting in prolonged EPOC have shown that the EPOC comprises only 6–15% of the net total exercise oxygen cost [36]. Laforgia et al. [36] have concluded that the major impact of exercise on body mass occurs via the energy expenditure accrued during actual exercise.” Results using HIIT have yet to be established.

Citation: Boutcher, S. H. (2010). High-intensity intermittent exercise and fat loss. Journal of obesity, 2011.