Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the newest and most widely used class of antidepressants on the market today. Furthermore, they are prescribed for more than the treatment of depression. Individuals with bioplar disorder may also be placed on a regimen of SSRIs to augment their primary medication, or in the case of PTSD and anxiety, used as the main pharmaceutical treatment. However, the general application of SSRIs for anxiety and conditions other than depression should be in question, especially since current research is changing the way we understand them.

Some quick background.

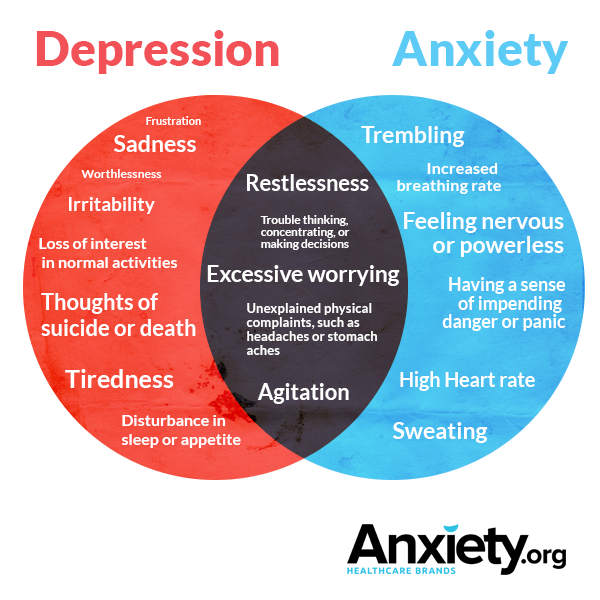

Serotonin is a neurotransmitter produced in the brain and gut, responsible for mood stabilization, feelings of calmness and general wellbeing. The scientific community still hasn’t reached a consensus on whether or not inadequate serotonin or serotonin receptor levels are the underlying causes for depression and anxiety, however, they have become the typical pharmacological treatment target for both disorders, even though they aren’t the same thing.

How do SSRIs work?

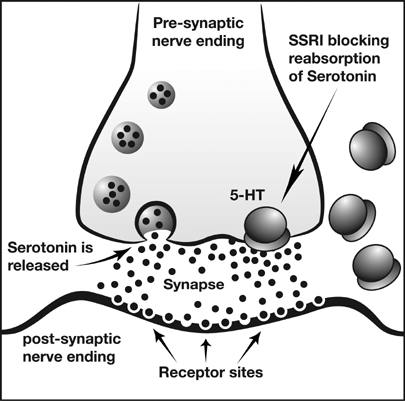

It is a common misconception that SSRIs simply increase the amount of serotonin available and therefore mood is improved. The drugs actually work by binding to proteins called serotonin transporters (SERTs) in the brain, which are responsible for recycling “used” serotonin, carrying it back to the message-sending neuron to be used again. By blocking the function of SERTs, more serotonin remains available and “free-floating” in the space between neurons, allowing more to be used for neuron-to-neuron message delivery. (For more, check out this interesting article in Scientific American.) Currently, there are six SSRIs available on the market: Celexa (citalopram), Lexapro (escitalopram), Luvox (fluvoxamine), Paxil (paroxetine), Prozac (fluoxetine), and Zoloft (sertraline).

Several studies in the late 90’s and early 2000’s used animal models to investigate the role of serotonin in anxiety, “knocking out” certain receptors in mice to see whether or not it affected their mood. Mice without the receptor 5HT1A, for example, exhibited fear-like behaviors and heightened anxiety.

So, what is the cause of anxiety?

Translate this into human conditions, and it could be assumed that we found the underlying cause physiological cause of anxiety disorders in people: low numbers of the 5HT1A serotonin receptor (although others may play a role), or low production of serotonin (not enough to bind to the receptor and cause the positive mood affects). Insert the application of of SSRIs.

But now, some researchers believe this previous theory may be somewhat incorrect – that some anxiety disorders may be caused by too much serotonin, not too little.

In 2015, researchers from Uppsala University and the Karolinska Institite in Sweden conducted a series of PET scans with C-11 tracer methodology to analyze serotonin production in patients diagnosed with social anxiety disorder. They specifically tracked influx rates “of [11C]5-HTP as a measure of serotonin synthesis rate capacity and [11C]DASB binding potential as an index of serotonin transporter availability.”

They compared the results to the same scans completed in a control group of individuals without the disorder. Their results, published in JAMA Psychiatry, show higher rates of serotonin synthesis in those with the anxiety disorder compared to those without it. Other studies are reaching the similar conclusions, debunking the widely accepted notion that anxiety, like depression, is due to low serotonin.

In 2016, the highly-regarded journal Nature published a study investigating the effects of Prozac on fear and anxiety in mice. They concluded that certain SSRIs, like Prozac, increase serotonin levels, effecting serotonin receptors that promote a negative change in mood:

“Examining the impact of SSRIs, the scientists exposed 2C-receptor BNST neurons to fluoxetine (Prozac), which like other SSRIs gives a boost to serotonin levels wherever the neurotransmitter is at work. This turned out to increase the 2C-receptor neurons’ inhibitory effect on the neighboring VTA- and LH-projecting neurons, worsening fear and anxiety behavior in mice.”

Step back a moment and apply the all of the aforementioned information. It seems to make sense that using the same pharmaceutical treatment method (SSRIs) for two mood disorders with different sets of symptoms – disorders we don’t fully understand the physiological cause of – could be the wrong approach, and perhaps ineffective.

What do YOU think?

References:

Frick, A., Åhs, F., Engman, J., Alaie, I., Björkstrand, J., Frans, Ö., … & Lubberink, M. (2015). Serotonin synthesis and reuptake in social anxiety disorder: a positron emission tomography study. JAMA psychiatry, 72(8), 794-802.

Marcinkiewcz, C. A., Mazzone, C. M., D’Agostino, G., Halladay, L. R., Hardaway, J. A., DiBerto, J. F., … & Tipton, G. J. (2016). Serotonin engages an anxi

Ramboz, S., Oosting, R., Amara, D. A., Kung, H. F., Blier, P., Mendelsohn, M., … & Hen, R. (1998). Serotonin receptor 1A knockout: an animal model of anxiety-related disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 95(24), 14476-14481.

Wow! Nice job Jenny! I think I’m with you. It doesn’t seem appropriate to use one treatment for two different conditions