A large majority of Americans have heard of the condition Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Despite its seemingly common prevalence, a lot of unanswered questions surround this particular dysfunction of the gut. Many individuals suffering from IBS lack a professional diagnosis and miss the foundational tools and understanding necessary to effectively deal with symptoms. Furthermore, IBS is a chronic disorder and can also be classified as a chronic pain syndrome, sometimes lasting for many years. Not only can it be difficult to control, but in more severe cases it may prevent travel and also hamper the ability to work.

The medical community has yet to reach a consensus on the etiology (cause) of IBS, and currently, there is no cure. A plethora of research exists supporting a dysfunction of the brain-gut axis, negative effects of dietary habits on nutrient absorption, and agreed-upon treatments that help make IBS a less prevalent issue in an individual’s daily life. Here, we discuss the possible causes for the disorder, situations that exacerbate the condition, and suggest ideas on how to regain some control over your body (and without surprise, it includes simple solutions such as exercise!)

What is IBS? According to the National Institutes of Health, IBS is a “functional gastrointestinal disorder.” This means it does not destroy the anatomy of the body (i.e. there no signs of damage to the intestine that may be seen with other diseases), but it does cause atypical function. A syndrome is a group of symptoms that always occur together. Understanding common symptomology allows medical professionals increased accuracy in diagnosing disease and stages of a disease. The primary symptoms associated with IBS are abdominal pain accompanied by a change in typical stool production, either diarrhea, constipation, or a mix.

Furthermore, IBS is categorized into four types based on the primary type of stool associated with it:

- IBS-C (with constipation)

- IBS-D (with diarrhea)

- IBS-M (mixed, i.e. both C and D)

- IBS-U (unsubtyped)

The (complex) pathophysiology… and psychosocial influence.

The mind-body connection is something STEM researchers (biologists, chemists, physiologists) used to push aside. Perhaps it was something to do with having a small regard for soft sciences like psychology and Eastern medicine, as evidence is more difficult to confirm and less is understood about the mind in comparison to the brain. But have you ever become queasy before a big exam or annual review from your boss? How about losing your appetite when feeling depressed? There are several diseases of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract associated with deviations away from a positive, balanced mental state, such as stress-related mucosal disease and gastric ulcers. Alterations in what is referred to as the “brain-gut axis” promote imbalance in neuro-endocrine functionality of the GI tract, leading to the onset of chronic syndromes like IBS.

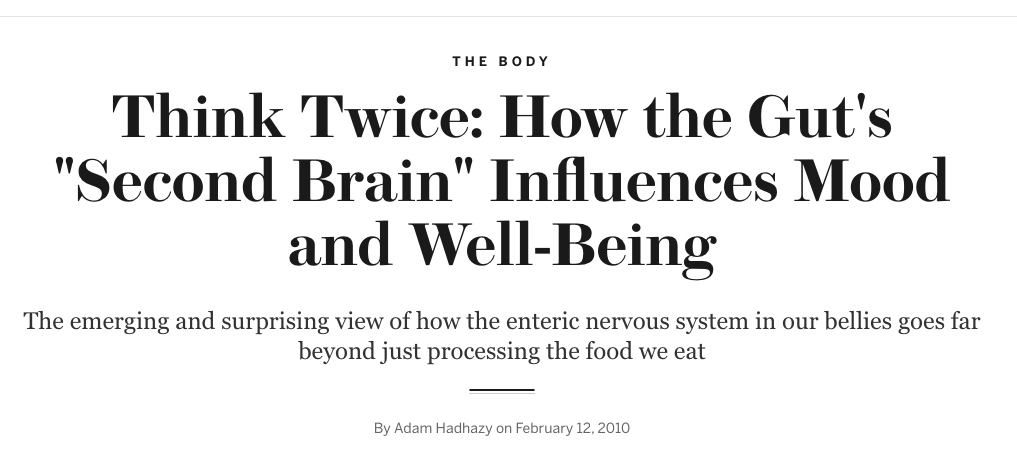

Your digestive system is governed by it’s own communication platform called the enteric nervous system (ENS, or enteric plexus). Consider it the direct link between the central nervous system (CNS) and what goes on in the digestive tract. The ENS is located within two layers of the digestive tract wall and controls blood flow, rate of digestion, secretion of digestive enzymes, as well as sensation, responding to changes in feeding status and stressors such as exercise. Studies have shown that ENS glial dysfunction (glia are nervous system support cells) plays a major role in GI motility abnormalities, the inflammatory response, and possibly symptoms associated with IBS.

The following fact is probably a surprise to many: approximately 80% of the body’s serotonin is made in the gut. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter responsible for transmission of nerve impulses, regulation of mood, appetite and GI function, and is also a precursor for the production of dopamine. It’s synthesized by ENS glial cells, and if too much or too little is present, or there is a dysfunction with the protein receptors that interact with it, symptoms of IBS-D may present themselves. See this interesting study published in 2001 by Dr. Jackie Wood, Ohio State University, for more.

All together, psychological mechanisms are thought to play a major part in triggering IBS, and understandably so. Stress, anxiety and depression have been supported as major triggers in disturbing the natural, homeostatic balance of the brain-gut axis, healthy levels of serotonin, and overall proper function of the ENS.

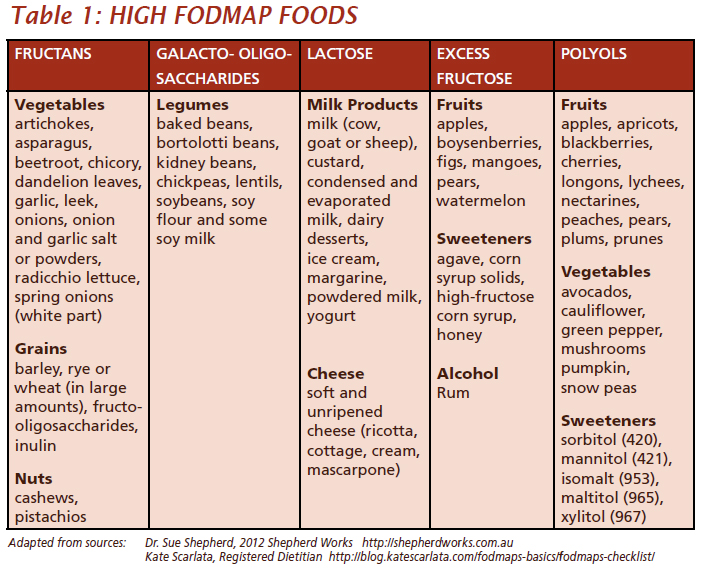

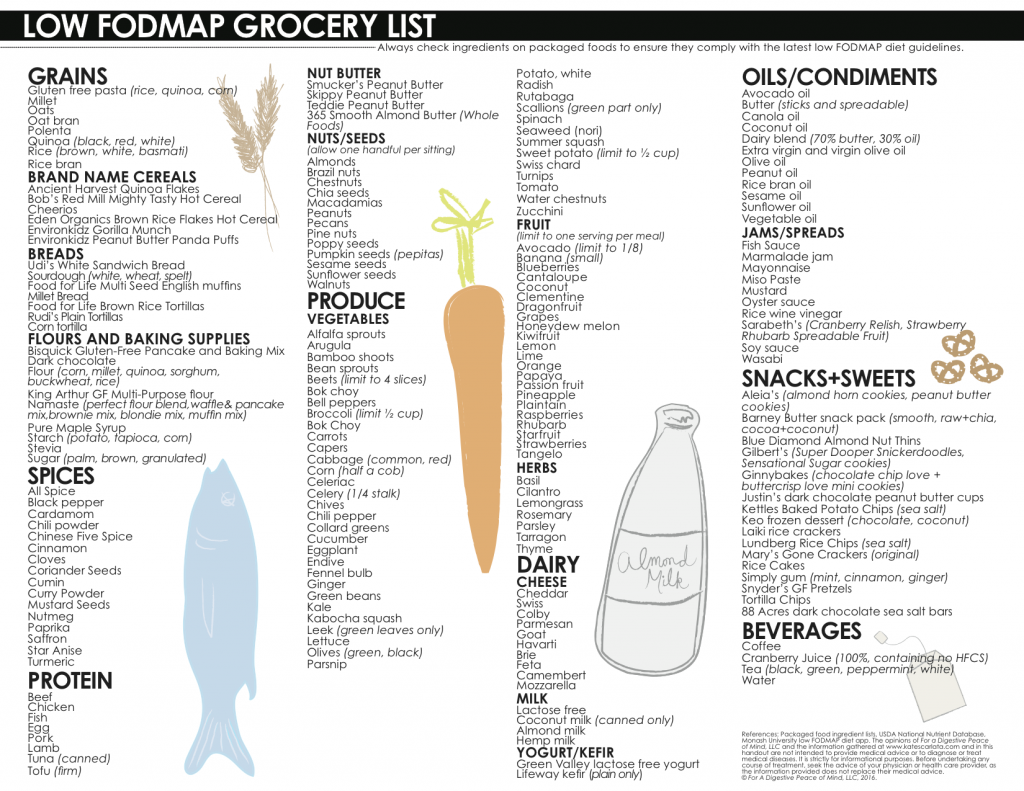

Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols. FODMAPs.

The acronym FODMAPs may be familiar to someone that suffers from IBS – but if not, it should be. And, don’t let the long name scare you. These molecules are a specific group of carbohydrates that are difficult for the small intestine to absorb. Lactose, fructans and fructose (in excess of glucose) are three examples of FODMAPs. They are found in many common foods such as milk, broccoli, some nuts and legumes, spanning several food groups.

When certain types of carbohydrates are not absorbed completely, they are left in the intestine to be fermented by certain types of gut bacteria. The fermentation process causes the production of gas (methane and hydrogen), leading to intestinal distention and a change in stool consistency. Imbalances in the gut microbiota are undoubtedly connected to IBS-associated GI dysfunction. Overgrowth of flora and the anticipated overproduction of methane may slow motility of foodstuffs through the GI tract, leading to symptoms associated with IBS-C.

A diet low in FODMAPs has been accepted by a large number of countries as a way to decrease and control symptoms associated with IBS. The scientific evidence supporting this dietary recommendation is sufficiently strong, and the physiological idea is this: eliminate “problem” foods that are not properly digested and absorbed, and symptoms will not present themselves.

Several studies have illustrated the association of fructose malabsorption with IBS onset. It has been generally agreed upon that an addition of fiber to the diet plays a large role in attenuating the presence of constipation in IBS-C, but may or may not help with abdominal pain and bloating. Also, not all foods are problems for everyone thanks to the somewhat ambiguous nature of the disease. Using a food diary and following recommendations on which foods to eliminate can help individualize treatment.

All this being said, there are some studies that challenge the scientific foundation of the FODMAPs diet (as this is the way with science). A 2012 study published in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology proposed that the intestinal distention associated with IBS may be associated with chemical additives. And what about the negative effects on microbiota balance when food groups are eliminated? Even with support from MRI and ileostomy-based studies, alternative patterns of thinking about the disease spawn some serious (and necessary) food for thought.

Gluten.

Unfortunately, there exists some conflicting evidence in regard to the elimination of gluten from the diet to help decrease the prevalence of IBS symptoms. It’s generally listed on the “Eliminate these foods!” lists given to many of those suffering from the disease (even though it isn’t a “food,” it’s a protein). What’s the opposing argument?

Thing one: Gluten is not a carbohydrate, so it cannot be classified as a FODMAP. (For more information on the gluten, celiac disease and associated elimination diets, check out our article, Gluten… Are You For Real?)

Thing two: Some recent research has shown some light on whether or not gluten has a negative effect on symptoms associated with IBS… and to some, it doesn’t. A 2013 study published in the journal Gastroenterology, performed a double-blind crossover trial (it doesn’t get much better than this), investigating whether or not gluten-containing foods affected individuals suffering from non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Ironically, gluten had no affect on symptoms. An earlier study in the same journal (2001) looked at sub-groups of IBS suffers that could benefit from gluten elimination due to a potential association with underlying celiac disease… but for those individuals only – not everyone. So is gluten elimination necessary? The jury is still out.

What about antidepressants? Or, exercise?

Low doses of specific antidepressants have been shown to provide some relief from an irritated gut. FDA-approved pharmaceuticals include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Take what was explained before regarding abnormal production and utilization of serotonin, and voila! – a theoretically useful prescription. The clinical community has shown some promising benefit in therapy, albeit imperfect.

But if SSRI’s are taken in low doses to help treat IBS, why not just exercise? Regular exercise has been shown to have the similar effects on mood as a prescription of low-dose antidepressants. It makes perfect sense that SSRI’s and exercise could both be co-prescribed as viable treatments for IBS. Exercise promotes the production of serotonin and dopamine, lifting mood and decreasing the negative effects of stress. Several controlled trials have shown positive effects of exercise on IBS-related symptoms. Furthermore, incorporating relaxation or meditation-based therapies such as yoga and tai chi have the same benefits on mental function as all of the former, and therefore the gut.

That mind-body connection… the brain-gut axis… if exercise was able to be packaged in a pill, it would be the most powerful prescription to promote wellbeing and create disease-less states.

References:

Barrett, J. S., & Gibson, P. R. (2012). Fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) and nonallergic food intolerance: FODMAPs or food chemicals?. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology, 5(4), 261-268.

Biesiekierski, J. R., Peters, S. L., Newnham, E. D., Rosella, O., Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2013). No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology, 145(2), 320-328.

Daley, A. J., Grimmett, C., Roberts, L., Wilson, S., Fatek, M., Roalfe, A., & Singh, S. (2008). The effects of exercise upon symptoms and quality of life in patients diagnosed with irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. International journal of sports medicine, 29(09), 778-782.

Furness, J. B., Callaghan, B. P., Rivera, L. R., & Cho, H. J. (2014). The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: integrated local and central control. In Microbial Endocrinology: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Health and Disease (pp. 39-71). Springer New York.

Halmos, E. P., Power, V. A., Shepherd, S. J., Gibson, P. R., & Muir, J. G. (2014). A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 146(1), 67-75.

Huether, S. E., & McCance, K. L. (2015). Understanding pathophysiology. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Irritable bowel syndrome. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved on Aug 19, 2016 from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/irritable-bowel-syndrome/Pages/overview.aspx

Jeffery, I. B., O’Toole, P. W., Öhman, L., Claesson, M. J., Deane, J., Quigley, E. M., & Simrén, M. (2012). An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut, 61(7), 997-1006.

Power, V. A., & Shepherd, S. J. (2014). Diet as a therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: progress at last. Gastroenterology, 146, 10-26.

Sharkey, K. A. (2015). Emerging roles for enteric glia in gastrointestinal disorders. The Journal of clinical investigation, 125(3), 918-925.

Shepherd, S. J., Parker, F. C., Muir, J. G., & Gibson, P. R. (2008). Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 6(7), 765-771.

Staudacher, H. M., Irving, P. M., Lomer, M. C., & Whelan, K. (2014). Mechanisms and efficacy of dietary FODMAP restriction in IBS. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology, 11(4), 256-266.

Wahnschaffe, U., Ullrich, R., Riecken, E. O., & Schulzke, J. D. (2001). Celiac disease–like abnormalities in a subgroup of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 121(6), 1329-1338.

Wood, J. D. (2001). Enteric nervous system, serotonin, and the irritable bowel syndrome. Current opinion in gastroenterology, 17(1), 91-97.

Hey, I love your post. I recently wrote an Blog Post on storing meat. I love to make my own food for Christmas!. We will be creating a basic ice cream to go with it. The teeny boppers will be on holiday and I am sure they are going to love it.

Pingback: CBD and Chronic Pain Syndrome • truPhys