The COVID-19 pandemic significantly illuminated gaps in the global care continuum. The identified gaps drove several outcomes, including a technological push to provide remote monitoring solutions outside the hospital in at-risk populations, including senior adults. One of the most preventable contributors to hospitalization in older adults is dehydration, a leader in admission rates for seniors over the age of 65. For hospitalized patients, dehydration has an estimated annual cost burden greater than $1.4 billion, in majority due to inadequate staffing and supervised care in skilled care and nursing facilities.

Unfortunately, dehydration often goes undetected until it manifests as a variety of consequential symptoms: confusion, falls, kidney injury, or cardiovascular instability. Unlike younger individuals, older adults do not always physiologically respond to thirst in a reliable way. As a result, dehydration in this population is less a failure of personal behavior than that of proactive detection and prevention.

As the global population ages, hydration management is emerging as a critical but under-addressed component of longevity. Water is often the forgotten macronutrient, even though the majority of adults understand it is needed in adequate amounts in order to sustain wellness, similar to healthy food-based calories. Advances in noninvasive biosensing now offer a way to objectively monitor hydration status in real time, enabling earlier intervention and more personalized care—particularly for vulnerable elderly populations.

Aging Physiology and Hydration Challenges

Hydration is defined as the physiological state in which total body water distribution across intracellular and extracellular compartments is sufficient to maintain normal plasma osmolality, electrolyte balance, cardiovascular function, thermoregulation, and cellular metabolism. Total body water is dynamic and maintained by a variety of systems and feedback loops. Dehydration is defined as a clinically significant deficit in total body water, leading to impaired cellular, renal and thermoregulatory function, cognitive impairment and cardiovascular instability.

In healthy younger adults, body water levels (hydration) are tightly regulated by osmoreceptors in the hypothalamus, which respond to subtle increases in plasma osmolality (a measure of the concentration of dissolved solutes in blood plasma). The major solutes that drive homeostatic blood osmolality are sodium, bicarbonate, chloride, glucose and urea.

Body water is regulated by stimulating thirst and the release of vasopressin (antidiuretic hormone, ADH). With aging, this feedback loop becomes less sensitive. Older adults demonstrate a blunted thirst response and altered neuroendocrine signaling. This can lead to reduced hypothalamic responsiveness to osmotic changes, delayed or absent perception of thirst (despite rising plasma osmolality), and altered vasopressin signaling and feedback dynamics that can lead to inadequate water conservation. As a result, older individuals may remain unaware of fluid deficits until dehydration is already clinically meaningful.

Changes in Body Composition and Total Body Water

Total body water decreases with age, largely due to an age-related loss of lean muscle mass, called sarcopenia. Adults lose approximately 1-4% of functional skeletal muscle per decade beginning around age 30, accelerating with age.

Muscle tissue is composed of roughly 76% water! A decline in muscle mass leads to a smaller physiological buffer against fluid loss. Further, older adults experience changes in the skin, a natural protective barrier, with a decrease in collagen concentration and production, and thinner subcutaneous fat layer.

A reduced overall compositional buffer increases vulnerability to heat illness. Further, even minor reductions in water intake, leading to under hydration can increase insensible waterless through a compromised barrier. Practically speaking, an older adult can become dehydrated more quickly and recovers more slowly than a younger individual under identical conditions.

Renal Aging and Loss of Fluid Reserve

Similar to a decline in neuroendocrine sensitivity and signaling, renal function also declines progressively with age. driven heavily by microvascular damage and structural changes including nephron loss and nephrosclerosis. Separate from age-related changes, roughly 34% of adults over age 65 have kidney disease.

The decline in renal function leads to a reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and the inability to concentrate or dilute urine, especially during physiological stress induced by heat exposure, illness or medication. What does this mean? Even modest fluid deficits can precipitate acute kidney injury in older adults, and over time, lead to the onset of chronic disease.

Cardio-Renal and Cognitive Effects

Hydration status is tightly linked to cardiovascular stability. Reduced kidney function impacts plasma volume maintenance. Couple that with any underlying cardiovascular disease, and a chicken and egg scenario may exist. Dehydration may lead to increased incidence of orthostatic hypotension, reduced cardiac output, and increased blood viscosity.

These effects raise the risk of falls, syncope, and potential ischemic events. Importantly, dehydration-related cerebral hypoperfusion can present as acute confusion, delirium, or worsening cognitive impairment—symptoms that are often misattributed to dementia progression rather than a reversible physiological insult.

What are the Problems with Hydration Management Today?

Traditional Hydration Indicators Fall Short

Hydration management is often approached using a reactive model. In at-risk populations, this limits opportunities for intervention.

1. Thirst is not a real-time indicator of hydration status. Generally, the sensation of thirst is perceived when functional body water loss approaches 2%. By this time, physical and cognitive performance is compromised and pronounced in older adults.

2. Urine color and output are commonly used hydration proxies but are influenced by medications (e.g. diuretics), overall renal function (e.g. CKD), and any associated co-morbidities (e.g. cardio-renal disease or CVD). Urinary markers may be misleading or delayed.

3. Traditional laboratory markers such as serum sodium and osmolality, urinary osmolality and urine specific gravity are useful but invasive, episodic, and often collected after dehydration is already present.

Practical Implications in Different Care Settings and the Role of Wearable Biosensors

In senior living environments, hydration monitoring is often dependent on staff observation and patient self-report (which for the myriad reasons already discussed, is not reliable). This is particularly problematic in assisted living and skilled nursing facilities for residents with dementia, mobility limitations and language barriers. Often, patients cannot communicate their needs and adequately hydrate themselves. Inadequacies among facility administration and staffing exacerbates the prevalence of dehydration. In clinical and transitional settings, such as following hospitalization, older adults are particularly vulnerable to dehydration because of medication, reduced mobility from bed rest or procedures, and altered routines.

Objective and remote monitoring of an individual’s hydration status could help identify at-risk adults and promote intervention prior to the onset of dehydration. A secondary outcome would be improved staff efficiency through prioritized intervention. Coupled with other biometrics, continuous monitoring could support safer transitions of care, reduce admission and readmission rates, and help deliver more precise fluid management strategies.

Momentum is gaining to increase at-home care outside the hospital setting through remote monitoring and the use of telehealth and related platforms. For older adults living independently, dehydration risk is frequently underestimated. Wearable hydration monitoring could provide early warnings during illness or heat exposure, and improve overall case management through personalized hydration guidance in place of generic recommendations. This is especially relevant for individuals managing chronic conditions such as heart failure, where both dehydration and overhydration carry risk, and medication management also plays a crucial role in body water maintenance.

Applications in Non-invasive Hydration Monitoring

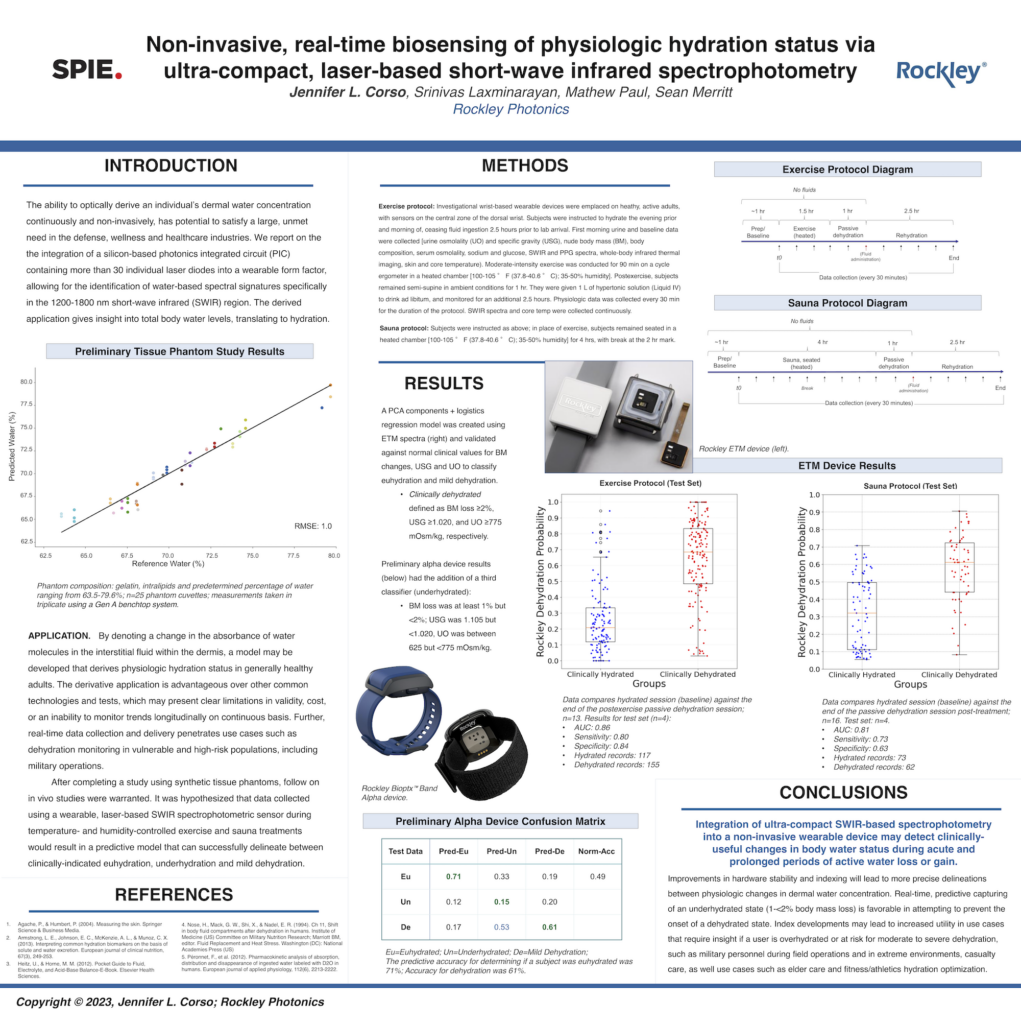

Most advances in optical sensing are currently providing noninvasive monitoring of hydration-related biomarkers through the skin. These platforms leverage multiple wavelengths of light to interrogate tissue at varying depths, capturing spectral features associated with blood volume, water, collagen, lipids, and/or solute concentration. By tracking these changes over time, wearable systems can generate individualized hydration indices that reflect real physiological status rather than population averages.

The true value of hydration monitoring lies not just in measurement, but in actionable insight. Modern platforms can incorporate data based on clinical biometrics, including body weight changes isolated to water loss, urinary markers including osmolality and specific gravity, among others. This information helps construct personalized data that can help detect early deviations from baseline hydration and contextualize any changes based on individual physiology.

Several wearable sensors found in modern watches and similar devices incorporate bioimpedance analysis (BIA), which can give a reasonable estimate of someone’s hydration status. BIA has been around for some time – it is often used to measure body composition in handheld devices and commercial scales. It is familiar, low cost, and provides a rapid measurement. However, known limitations exist that impact reliability of the data, including factors such as environmental humidity, and electrolyte and sweat composition.

Advancements in optical-based techniques such as infrared spectroscopy and NIRS, LED-based approaches and semiconductor photonic sensors are targeting different biometrics, such as water content, sweat and water absorption peaks. Unlike BIA or other electrochemical sensors and patches, which often rely on the presence of sweat, continuous monitoring or physical activity, these are cost-effective, versatile, convenient and practical solutions for real-time monitoring, and are often coupled with additional biometrics for a more robust health analysis. Though limitations in all non-invasive measurements exist, particularly those that target whole-body metrics through the skin, the biotechnical advances are incredibly promising.

For older adults and their caregivers, data from remote monitoring platforms can transform hydration into a measurable, manageable aspect of health. Dehydration in older adults is not an inevitable consequence of aging—it is a solvable problem rooted in physiology, healthcare system design and remote sensing technology. By pairing a deeper understanding of age-related hydration dynamics with continuous, noninvasive monitoring platforms, an opportunity opens to reduce healthcare system burden, improve case management, preserve cognitive and physical function, and maintain quality of life well into advanced age. Objective hydration monitoring may prove to be one of the most impactful and underappreciated tools in preventive care.

References:

Belabbaci, N. A., Anaadumba, R., & Alam, M. A. U. (2025). Recent Advancements in Wearable Hydration-Monitoring Technologies: Scoping Review of Sensors, Trends, and Future Directions. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 13, e60569. https://doi.org/10.2196/60569

Corso, J. L. (2022). How Wearables Will Revolutionize Hydration Management. truPhys.com. Retrieved from https://truphys.com/how-wearables-will-revolutionize-hydration-management/

Corso, J. L., Paul, M., Laxminarayan, S., & Merritt, S. (2023, June). Non-invasive, real-time biosensing of physiologic hydration status via ultra-compact, laser-based short-wave infrared spectrophotometry. In Next-Generation Spectroscopic Technologies XV (Vol. 12516, p. 1251610). SPIE.

Corso, J. L., & Peikon, E. (2025). The Challenge of Measuring Exercise: Advancing Metrological Barriers in Wearable Sensing. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 13(1), e79347. doi: 10.2196/79347

Kayser‐Jones, J., Schell, E. S., Porter, C., Barbaccia, J. C., & Shaw, H. (1999). Factors contributing to dehydration in nursing homes: inadequate staffing and lack of professional supervision. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(10), 1187-1194. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05198.x

Seal, A. D., Colburn, A. T., Johnson, E. C., Péronnet, F., Jansen, L. T., Adams, J. D., Bardis, C. N., Guelinckx, I., Perrier, E. T., & Kavouras, S. A. (2023). Total water intake guidelines are sufficient for optimal hydration in United States adults. European journal of nutrition, 62(1), 221–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-022-02972-2

United States Renal Data System. 2023 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2023

Wilkinson, D. J., Piasecki, M., & Atherton, P. J. (2018). The age-related loss of skeletal muscle mass and function: Measurement and physiology of muscle fibre atrophy and muscle fibre loss in humans. Ageing research reviews, 47, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2018.07.005